Installation Video

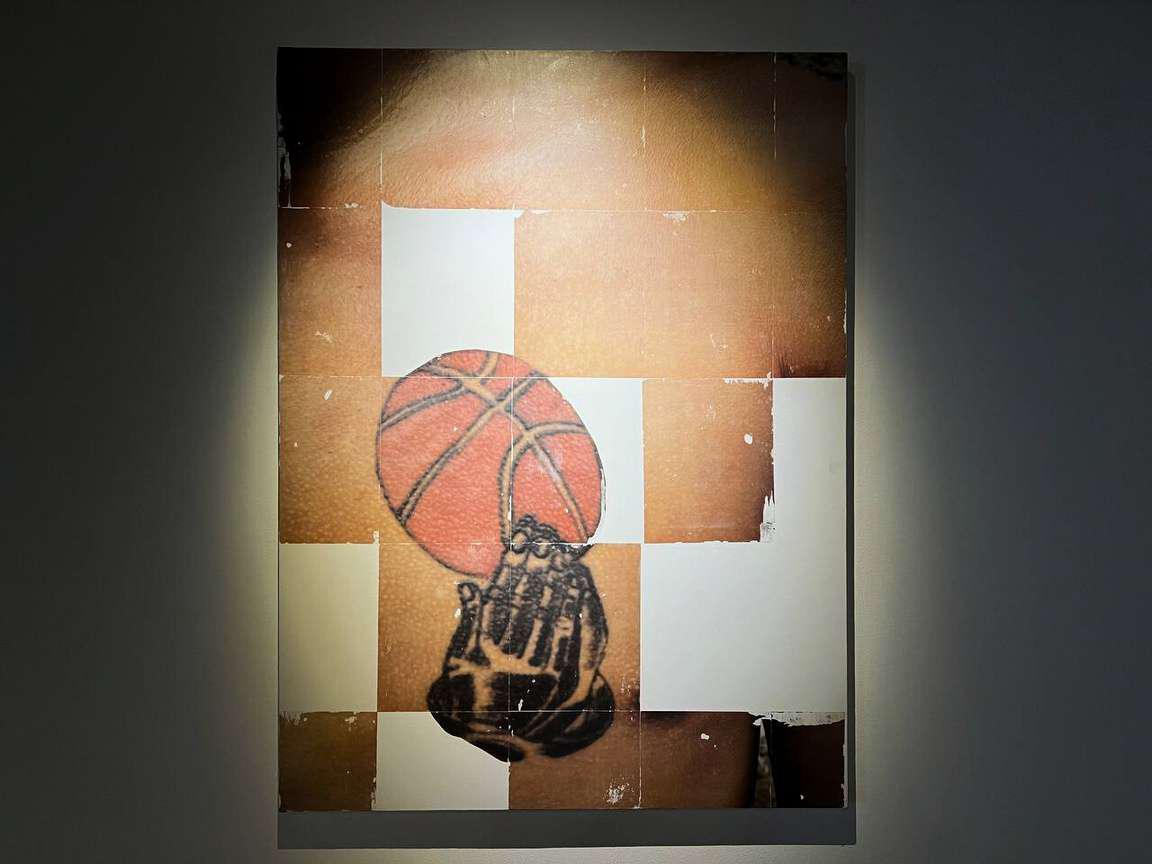

Signs of the Crossover

notes written by Nicole Soriano-Lao

Welcome to Basketball Country: where a song dedicated to a local basketball team pleads to the saints for a win. Where you walk on the street and chance upon a player wearing a scapular with his jersey, or a tattoo of a basketball atop hands clasped in prayer on his chest.

For his solo exhibition Signs of the Crossover, artist Charles Salazar investigates the powerful relationship between basketball and belief in the Philippines. Through a mix of collage, video, and installation works, he expands a theme that has been central to his artistic practice—how basketball culture impacts the daily life of Filipinos.

Basketball lives in almost every corner of the country, from urban shanty towns to fishing villages to jails. And yet, Filipinos are perceived as a kind of underdog in the sport on the global stage, with many claiming our short height as a disadvantage. Sociologist Lou Antolihao paints an apt metaphor: “small players” against their bigger opponents, mirroring Filipinos’ struggle against giant forces of colonialism and poverty. A nearly impossible match. Yet, Filipinos’ passion for basketball goes beyond the thrills of a win: it is, Antohilao argues, a celebration of subversion. Sports journalist Recah Trinidad calls it a “ritual of defiance”—one that he claims originated in 1521, when Lapu-Lapu allegedly defeated Ferdinand Magellan against the odds. Salazar calls it an act of enormous faith.

In the eponymous work Signs of the Crossover, Salazar presents a montage of different professional basketball players mid-game, filmed in grainy 16mm. They’re captured, however, not whilst shooting a hoop or dribbling a ball, but performing what has become a signature move on Philippine basketball courts: the sign of the cross. Yet, to watch each player perform the same sign of worship in an endless loop forces us to see a rare side of them—their belief. It may root in religion, or other forms of spirituality. But one thing’s certain: Filipino players rely not only on physical strength, but a preternatural one. It’s a kind of strength that perhaps fuels them to keep playing, despite traditional notions of “basketball glory” being so distant from their makeshift hoops and flip-flops.

In Hail and Hail Kings, an installation of chairs forms a cross, with each chair wearing a different basketball jersey. The work evokes, this time, the faith of fans. Spectators who, as the song Kapag Natatalo ang Ginebra (When Ginebra Loses) narrates, religiously follow each game even as their team struggles. What kind of faith does it take to worship heroes that will most likely face defeat?

“The coliseum, just like the church, provides the basketball fan a sense of community and belonging, inspired by rituals that celebrate suffering and sacrifice, and a promise that underdogs will have a chance to redeem themselves in the end,” writes Antolihao.

Just as they did with religion, colonizers used basketball as a tool to “civilize” Filipinos. Yet, Signs of the Crossover captures how Filipinos took the very things used to control us, and used them to resist. A turnaround, if you will. A swerve. A crossover